Migrants have become a flashpoint in global politics. But new research by an MIT political scientist, focused on West Germany and Poland after World War II, shows that in the long term, those countries developed stronger states, more prosperous economies, and more entrepreneurship after receiving a large influx of immigrants.

Those findings come from a close examination, at the local level over many decades, of the communities receiving migrants as millions of people relocated westward when Europe’s postwar borders were redrawn.

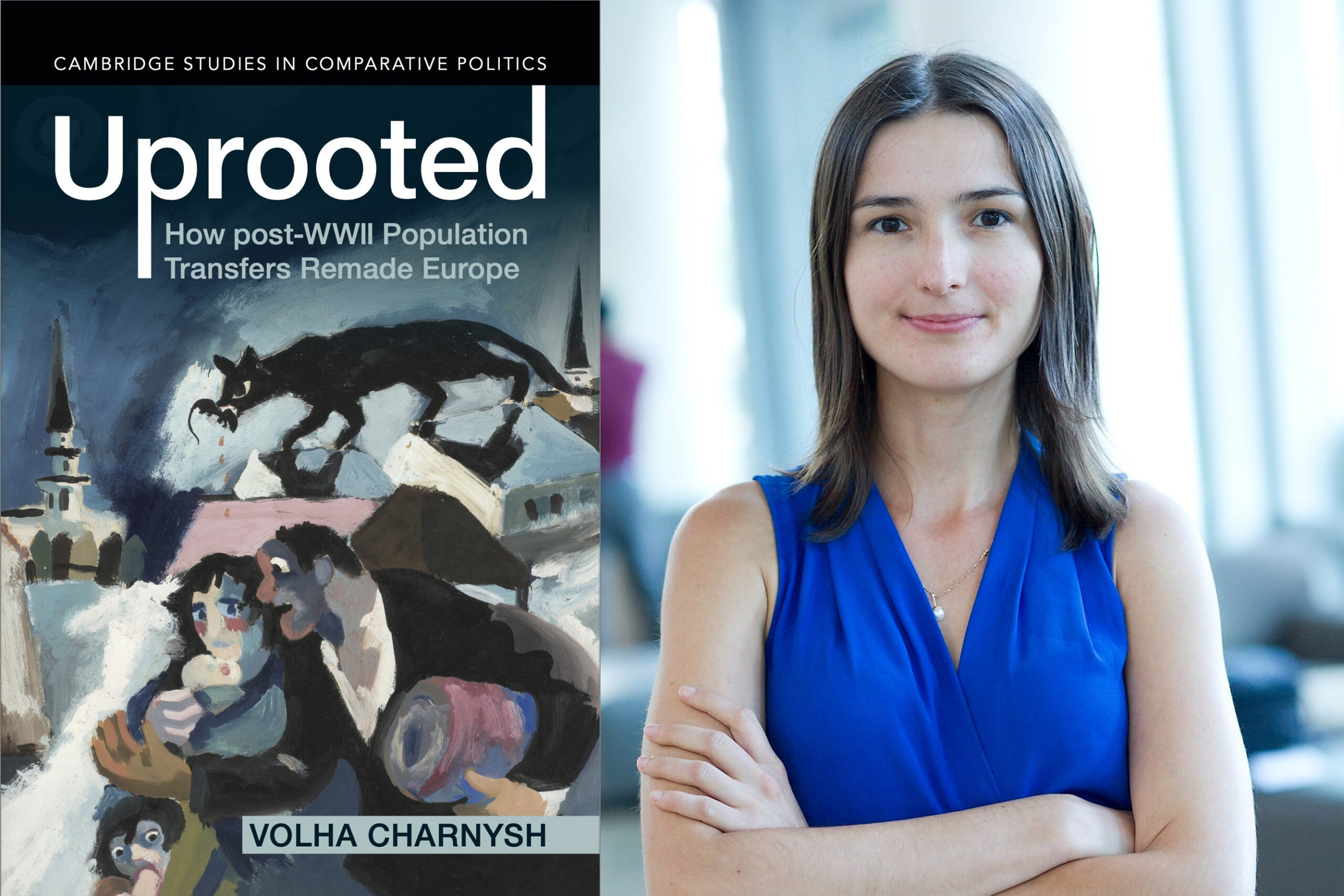

“I found that places experiencing large-scale displacement [immigration] wound up accumulating state capacity, versus places that did not,” says Volha Charnysh, the Ford Career Development Associate Professor in MIT’s Department of Political Science.

Charnysh’s new book, “Uprooted: How Post-WWII Population Transfers Remade Europe,” published by Cambridge University Press, challenges the notion that migrants have a negative impact on receiving communities.

The time frame of the analysis is important. Much discussion about refugees involves the short-term strains they place on institutions or the backlash they provoke in local communities. Charnysh’s research does reveal tensions in the postwar communities that received large numbers of refugees. But her work, distinctively, also quantifies long-run outcomes, producing a different overall picture.

As Charnysh writes in the book, “Counterintuitively, mass displacement ended up strengthening the state and improving economic performance in the long run.”

Extracting data from history

World War II wrought a colossal amount of death, destruction, and suffering, including the Holocaust, the genocide of about 6 million European Jews. The ensuing peace settlement among the Allied Powers led to large-scale population transfers. Poland saw its borders moved about 125 miles west; it was granted formerly German territory while ceding eastern territory to the Soviet Union. Its new region became 80 percent filled by new migrants, including Poles displaced from the east and voluntary migrants from other parts of the country and from abroad. West Germany received an influx of 12.5 million Germans displaced from Poland and other parts of Europe.

To study the impact of these population transfers, Charnysh used historical records to create four original quantitative datasets at the municipal and county level, while also examining archival documents, memoirs, and newspapers to better understand the texture of the time. The assignment of refugees to specific communities within Poland and West Germany amounted to a kind of historical natural experiment, allowing her to compare how the size and regional composition of the migrant population affected otherwise similar areas.

Additionally, studying forced displacement — as opposed to the movement of a self-selected group of immigrants — meant Charnysh could rigorously examine the scaled-up effects of mass migration.

“It has been an opportunity to study in a more robust way the consequences of displacement,” Charnysh says.

The Holocaust, followed by the redrawing of borders, expulsions, and mass relocations, appeared to increase the homogeneity of the populations within them: In 1931 Poland consisted of about one-third ethnic minorities, whereas after the war it became almost ethnically uniform. But one insight of Charnysh’s research is that shared ethnic or national identification does not guarantee social acceptance for migrants.

“Even if you just rearrange ethnically homogenous populations, new cleavages emerge,” Charnysh says. “People will not necessarily see others as being the same. Those who are displaced have suffered together, have a particular status in their new place, and realize their commonalities. For the native population, migrants’ arrival increased competition for jobs, housing, and state resources, so shared identities likewise emerged, and this ethnic homogeneity didn’t automatically translate into more harmonious relations.”

Yet, West Germany and Poland did assimilate these groups of immgrants into their countries. In both places, state capacity grew in the decades after the war, with the countries becoming better able to administer resources for their populations.

“The very problem, that migration and diversity can create conflict, can also create the demand for more state presence and, in cases where states are willing and able to step in, allow for the accumulation of greater state capacity over time,” Charnysh says.

State investment in migrant-receiving localities paid off. By the 1980s in West Germany, areas with greater postwar migration had higher levels of education, with more business enterprises being founded. That economic pattern emerged in Poland after it switched to a market economy in the 1990s.

Needed: Property rights and liberties

In “Uprooted,” Charnysh also discusses the conditions in which the example of West Germany and Poland may apply to other countries. For one thing, the phenomenon of migrants bolstering the economy is likeliest to occur where states offer what the scholars Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson of MIT and James Robinson of the University of Chicago have called “inclusive institutions,” such as property rights, additional liberties, and a commitment to the rule of law. Poland, while increasing its state capacity during the Cold War, did not realize the economic benefits of migration until the Cold War ended and it changed to a more democratic government.

Additionally, Charnysh observes, West Germany and Poland were granting citizenship to the migrants they received, making it easier for those migrants to assimilate and make demands on the state. “My complete account probably applies best to cases where migrants receive full citizenship rights,” she acknowledges.

“Uprooted” has earned praise from leading scholars. David Stasavage, dean for the social sciences and a professor of politics at New York University, has called the book a “pathbreaking study” that “upends what we thought we knew about the interaction between social cohesion and state capacity.” Charnysh’s research, he adds, “shows convincingly that areas with more diverse populations after the transfers saw greater improvements in state capacity and economic performance. This is a major addition to scholarship.”

Today there may be about 100 million displaced people around the world, including perhaps 14 million Ukrainians uprooted by war. Absorbing refugees may always be a matter of political contention. But as “Uprooted” shows, countries may realize benefits from it if they take a long-term perspective.

“When states treat refugees as temporary, they don’t provide opportunities for them to contribute and assimilate,” Charnysh says. “It’s not that I don’t think cultural differences matter to people, but it’s not as big a factor as state policies.”